Spanish immigration to France in the 20th century

Throughout the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of Spaniards emigrated to France looking for better living conditions. The political and economic development of the societies they left and arrived in had a huge effect on their future and their decision to settle definitively in France, or not.

Legende

Passage Boise, La Plaine Saint-Denis, circa 1926. Itinerant photographer.

Credit

© Collection Natacha Lillo

1914-1945: a notable presence

Spaniards have been immigrating to France since the late 19th century, especially in the border regions. They mainly worked on farms in the Midi, and in agriculture or industry in the South-West. Others were already living in the urbanised and industrialised areas of the Bouches-du-Rhône, Rhône and Seine, but represented a much smaller proportion.

World War 1 accelerated things greatly: their numbers went from 106,000 to 255,000 between 1911 and 1921. Spain did not take part in the conflict, but took advantage of it to sell farm products to the warring countries, which led to a dramatic increase in prices for the population. The majority of migrants worked in agriculture in the border regions, but some of them went further north to work in ordinance factories. They had to cope with precarious working and housing conditions and most of them returned home in 1918. However, noticing that the situation in Spain had not improved, many of them went back to France from 1919, this time taking their families with them.

Construction site in La Plaine Saint-Denis, where many Spaniards were employed in 1926. Itinerant photographer.

© Collection particulière. Source: Natacha Lillo

In the 1920s, the Spanish presence consistently increased through the migration network system. From 1921, they represented the third largest foreign nationality in France. In 1926, three-quarters of the 322,000 Spaniard were living south of the Bordeaux-Marseille line. Almost all of them came from nearby regions: people from Catalonia, Aragon and Levante in Languedoc-Roussillon, Basques or Navarrese in Aquitaine.

The sectors that Spanish migrants worked in

In 1931, 55,000 Spanish immigrants were working in agriculture (30% of the working population), especially in the vineyards of the Midi. Most were day labourers. A lot of them had worked in France before during the grape harvests, which employed between 15,000 and 18,000 Spanish seasonal workers per year. Over the years, some of them managed to save enough to buy land: in 1938, France counted 17,000 Spanish farm owners, 5,000 of them in the Eastern Pyrenees.

Legende

Spanish family in La Plaine Saint-Denis in the early 1930s

Credit

© Collection particulière Angeles S. C. Source: Natacha Lillo

But the majority of Spaniards tended to live in industrialised departments (Seine, Rhône, Isère, etc.). In 1931, 85,000 Spaniards were employed in industry (44% of the working population) and 19,000 in construction (10% of the working population). They were generally labourers in the steel industry and metallurgy (13,000), glassworks (6,100), the textile industry (6,000), mines in the South (6,500) and industrial chemistry (5,700). Only 25% of Spanish workers were skilled, as opposed to 75% of the French workers.

Unlike members of other immigrant communities, Spaniards tended to group together in areas where they were often the majority, like Petite Espagne in Plaine Saint-Denis or the Saint-Michel district of Bordeaux. This immigrant community had a very strong family component: the men arrived first to find a job and housing, then brought their wives and children along.

Between return and integration

The crisis of 1929 put an end to the policy of openness to foreigners that had been established after the losses of World War 1. In 1932, a series of decrees established quotas in industry and services and unemployed foreigners risked being extradited. Between 1931 and 1936, the number of Spaniards in France went from 352,000 to 254,000, a drop that can also be explained by the proclamation of the Second Republic in Spain in 1931: confronted with unemployment and growing xenophobia, many immigrants decided to return home, trusting in the Republic’s promises.

Legende

Application for naturalization of José Pascual and his wife, née Joséphine Combes, Spanish citizens, 1929; document held at the Archives nationales, Paris (shelfmark 5-014).

Credit

© Cliché Atelier photographique des Archives nationales

Meanwhile, these difficulties also gave rise to a heavy increase in requests for naturalisation, especially among Spanish men married to a Frenchwoman and those whose job was threatened by quotas.

The vast majority of families who stayed in France during the crisis of the 1930s never returned to Spain. The civil war, World War 2 and the closing of the Pyrenean border until 1948 led to the loss of links with the Spanish Peninsula. And they were particularly encouraged to stay by the fact that, with France under reconstruction, their children could find good jobs: young men whose fathers were unskilled workers were able to find skilled jobs in industry; as for the young women, most of them entered the job market, often in the service sector, whereas their mothers had been housewives their whole lives. This social climbing came hand in hand with a very large number of mixed marriages, the reflection of successful integration.

The massive influx of the 30-year post-war boom

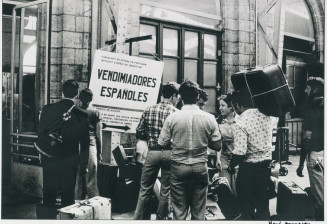

Perpignan 1975, arrival of Spanish grape-pickers

© Hervé Donnezan/Rapho/Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration

From 1945, the number of clandestine crossings through the Pyrenees increased: these were political but also, increasingly, “economic” refugees. But it was only after 1956, with the creation of the Spanish Institute for Emigration (SIE) that the migration flow started to grow again. The number of arrivals rose sharply from 1960. In 1968, the 607,000 Spaniards living in France represented the leading foreign nationality.

Characteristics shared with interwar emigration…

In the provinces with a strong migration tradition, the first to leave were people born in France in the 1920s and 1930s whose parents had returned to France after the economic crisis and the proclamation of the Republic. In many cases, some of their family had stayed in France and could help them to find housing, a job and to obtain residence permits.

As a result, some of the areas with a strong Spanish presence recreated the connections that had been broken for some twenty years and the migration networks began to operate again.

Once again, these men had few qualifications, farmworkers or very small landowners, and were hired at the bottom of the ladder in the automobile, steel and construction industries. At the beginning of their stay, they experienced housing problems: some of them had to live in shanty towns in the suburbs of Lyon and Paris, while others were piled inside attic rooms, caretaker’s apartments or cheap furnished rooms. Around 1975, access to the social housing became easier and building workers sometimes built their own individual home.

The creation of the SIE by the Francoist dictatorship showed its determination to control emigration, since its purpose was to monitor departures by signing contracts with entrepreneurs in the host countries. Although it represented only a tenth of departures to France, this “assisted” emigration enabled people who did not have access to the networks forged since the interwar period, and especially Andalusians and Galicians, to leave.

… and some differences

In the 1960-1970s, the distribution of Spaniards across France changed, notably with a reduction in the disproportionate numbers in the South, due to a lower demand for labour. Hence, their presence in the Paris region exploded due to the needs of the automobile, building and domestic service sectors (in 1968, a quarter of registered Spaniards were living in Ile-de-France, 65,500 of them in the city of Paris). The SIE also sent workers to work in the mines of the North or East, in the Michelin companies in Clermont-Ferrand or Citroën in Rennes, regions where the Spanish presence had previously been very limited.

But the most striking new fact about this emigration was the large presence of women by themselves who had come to work in domestic service. Whereas during the interwar period, they emigrated still accompanied by their fathers, husbands or brothers, now many of them left alone or with a sister or a cousin.

Daily life of a Spanish maid in Paris, 1962, Jean-Philippe Charbonnier

© Musée national de l'histoire de l'immigration

Many of them were single, but married women were also pioneers in family emigration: once placed and housed in an attic room, they had their husband and even their children join them. While Paris and Neuilly-sur-Seine welcomed the majority of them, others settled in Bordeaux, Lyon or Lille.

In the 1960s and 1970, the percentage of Spanish women working was much higher in France than in Spain and couples, obsessed by the idea of a return, chose this strategy so they could save up the necessary amount more quickly.

Many return to Spain

During the interwar period, the wages of farm day labourers or unskilled workers gave them just the means to reproduce their workforce and trips to Spain were rare because they were expensive. However, thanks to the different types of social benefits granted to foreign workers from the 1950s along with the increase in wages, the immigrants of the thirty post-war boom years were able to save enough to return home each summer. In the 1970s, they often purchased property.

Legende

Poster published by the Office national des migrations, 1980

Credit

© Collection Génériques

Unlike migrants during the interwar period for whom re-emigration to Francoist Spain was scarcely conceivable, the economic and political developments of the 1970s led to many returns. As was the case in the 1930s, two factors were converging: the consequences in France of the economic crisis of 1973 and, in Spain, of the transition to democracy from 1975. In 1974, the French government voted in a law ending work-related immigration and encouraged returns, allocating 10,000 francs to anyone willing to leave their job, which many Spaniards took advantage of; by 1982, only 321,000 of them remained, compared to 498,000 in 1975.

Other immigrants did not want to go home before ending their career in France in order to obtain a better retirement pension, and kept living there. However, from the 1980s, many young people born in France decided to go and live in Spain on reaching adulthood, whereas in some cases they only had French nationality and their parents were still living in France. Some chose Spain, attracted by the sun, others because this EU country had a dynamic economy until 2008. Perhaps some also left because the French "integration machine" had ground to a halt...

Natacha Lillo, Paris Sorbonne Cité Paris Diderot

Find out more about Spaniards in the Resistance:

Oral archives: Interview with Léontine Arenas